15 August 2006

Fountain

This lovely little installation is on view at Wave Hill right now. Whenever I see a solar panel used like this, though, I can't help but wish it were powering something useful. Not that art for art's sake isn't valuable. It's just that my thoughts these days always go immediately to "what can we take off the grid?" and "silicon doesn't grow on trees, you know."

This lovely little installation is on view at Wave Hill right now. Whenever I see a solar panel used like this, though, I can't help but wish it were powering something useful. Not that art for art's sake isn't valuable. It's just that my thoughts these days always go immediately to "what can we take off the grid?" and "silicon doesn't grow on trees, you know."What can I say? I'm obsessed.

13 August 2006

Wave Hill

It had been a while since I took a proper long walk, and since Sunday's weather could not have been more perfect, I decided to get myself up to the Bronx to visit Wave Hill. After emerging from the 1 train at the end of the line -- 242nd Street and Broadway, the southwestern corner of Van Cortlandt Park -- I took a left turn on 246th Street, figuring that somehow, though it wasn't clear from the map I consulted how this would happen since the Henry Hudson Parkway was between me and it, I'd be able to get all the way west to Wave Hill.

It had been a while since I took a proper long walk, and since Sunday's weather could not have been more perfect, I decided to get myself up to the Bronx to visit Wave Hill. After emerging from the 1 train at the end of the line -- 242nd Street and Broadway, the southwestern corner of Van Cortlandt Park -- I took a left turn on 246th Street, figuring that somehow, though it wasn't clear from the map I consulted how this would happen since the Henry Hudson Parkway was between me and it, I'd be able to get all the way west to Wave Hill. The Bronx is incredibly hilly. I seemed to have walked up a 45 degree angle the entire length of 246th Street, which winds its way through the private neighborhood of Fieldston. If you want to know where the mythical upscale areas of the Bronx are, here is one. Enormous, but graceful houses on well-tended lawns.

There's nothing ostentatious about it, but it's clear this is a very wealthy place. Oddly, I only saw one family, exiting from a minivan; otherwise, no one seemed to be home. I'm not sure what it means that it's a "private" neighborhood -- are these not city streets? I think it means that the private security guards who patrol in unmarked cars could make things uncomfortable if they didn't like the look of you.

There's nothing ostentatious about it, but it's clear this is a very wealthy place. Oddly, I only saw one family, exiting from a minivan; otherwise, no one seemed to be home. I'm not sure what it means that it's a "private" neighborhood -- are these not city streets? I think it means that the private security guards who patrol in unmarked cars could make things uncomfortable if they didn't like the look of you.  Between the hills and the dead ends, it took a while to wend my way to Wave Hill, but it was worth it. Wave Hill is one of the city's hidden jewels. Formerly the summer estate of a succession of prominent families (Teddy Roosevelt spent time there, as did Mark Twain), it's now a series of gardens and greenhouses on gently rolling ground that overlooks the Hudson River.

Between the hills and the dead ends, it took a while to wend my way to Wave Hill, but it was worth it. Wave Hill is one of the city's hidden jewels. Formerly the summer estate of a succession of prominent families (Teddy Roosevelt spent time there, as did Mark Twain), it's now a series of gardens and greenhouses on gently rolling ground that overlooks the Hudson River.

There's a small woodsy area, and the two manor houses now contain art galleries and educational programs. Most of the other visitors seemed to be regulars, sitting under trees on the wooden chairs scattered on the lawn, reading the Sunday paper.

08 August 2006

Lieberman vs. Lamont

They're voting today in Connecticut in the Democratic primary. Joe Lieberman, coming to the end of his third Senate term, is being challenged by businessman Ned Lamont, who opposes Lieberman's support of the war in Iraq.

Much has been made of the role that liberal blogs have played in building up the Lamont candidacy -- or rather, in tearing down of Lieberman's -- and what it means for the future of the Democratic party. Will the blogosphere succeed in defeating long-term Democratic politicians in the primaries at the expense of their party winning in the general election in the fall?

I've always been one of those wishy-washy Democrats, who are intellectually and emotionally liberal, but pragmatic when it comes to strategy and voting. Pragmatic, in the last decade or so, has meant supporting candidates who are indistinguishable half the time from Republicans, and how well has that served us?

If I were in Connecticut, I'd be voting for Lamont, mostly on the war issue, even though the loss of Lieberman in the Senate will mean losing his seniority on several committees, which is the aspect of being a Senator most directly beneficial to his constituents (think: pork, or as they more genteely call it, earmarks).

But I'd also be voting against Lieberman, whose cynicism in the 2000 election was breathtaking -- remember that he stood for reelection to his Senate seat at the same time that he was on the ballot to be Al Gore's Vice President -- and whose self-righteous pomposity is as infuriating as it is inappropriate. We didn't need to hear his sermon from the Senate floor about the sins of Bill Clinton. We didn't need to be lectured about the moral imperative of the government to intervene in the Terry Schiavo case.

And if Lamont wins today, but loses in November? Sadly, with the George Bush still in the White House, I'm not sure it matters what the rest of the government is doing.

Much has been made of the role that liberal blogs have played in building up the Lamont candidacy -- or rather, in tearing down of Lieberman's -- and what it means for the future of the Democratic party. Will the blogosphere succeed in defeating long-term Democratic politicians in the primaries at the expense of their party winning in the general election in the fall?

I've always been one of those wishy-washy Democrats, who are intellectually and emotionally liberal, but pragmatic when it comes to strategy and voting. Pragmatic, in the last decade or so, has meant supporting candidates who are indistinguishable half the time from Republicans, and how well has that served us?

If I were in Connecticut, I'd be voting for Lamont, mostly on the war issue, even though the loss of Lieberman in the Senate will mean losing his seniority on several committees, which is the aspect of being a Senator most directly beneficial to his constituents (think: pork, or as they more genteely call it, earmarks).

But I'd also be voting against Lieberman, whose cynicism in the 2000 election was breathtaking -- remember that he stood for reelection to his Senate seat at the same time that he was on the ballot to be Al Gore's Vice President -- and whose self-righteous pomposity is as infuriating as it is inappropriate. We didn't need to hear his sermon from the Senate floor about the sins of Bill Clinton. We didn't need to be lectured about the moral imperative of the government to intervene in the Terry Schiavo case.

And if Lamont wins today, but loses in November? Sadly, with the George Bush still in the White House, I'm not sure it matters what the rest of the government is doing.

06 August 2006

How much is enough?

We had a heat wave in New York this week. Temperatures were in the 90s every day; with the humidity, it felt like it was in the 100s. The air did not move; it settled down on top of us, making it hard to breathe.

Mayor Bloomberg implored everyone to reduce their use of electricity, lest we overload the grid and cause a blackout. In 2003 we had one that affected the entire city for three days. With the rest of the country suffering in the same way last week, it was not unlikely that we'd lose power.

Most of us didn't, though, thanks to some conservation, and luck. Apparently businesses responded fairly well to the Mayor's pleas. My office building turned up the air conditioning a few degrees and turned off non-essential lights. The Empire State and Chrysler Buildings were not lit up as they usually are. Retail shops still blasted their a/c high enough to be felt on the street, but enough other people pitched in to make it work.

Who didn't respond at all heroically, though, was the general population. Electric usage went up after 6pm, when people got home and cranked up their a/c.

On the one hand, who can blame them? It was miserable. Just the walk from the subway took a couple of hours to recover from.

However, I couldn't help but think: this is it, folks. Do you think it's going to get, on the whole, cooler in the years to come? Do you think we're modernizing our electric plants fast enough to keep up with increased demand? Do you think coal and oil will last forever, and even if they do, that it's a good thing to be pumping more and more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere?

We should be conserving every day, not just when there's an emergency. The problem is, no one is asking us to; no one is telling us to.

Mayor Bloomberg implored everyone to reduce their use of electricity, lest we overload the grid and cause a blackout. In 2003 we had one that affected the entire city for three days. With the rest of the country suffering in the same way last week, it was not unlikely that we'd lose power.

Most of us didn't, though, thanks to some conservation, and luck. Apparently businesses responded fairly well to the Mayor's pleas. My office building turned up the air conditioning a few degrees and turned off non-essential lights. The Empire State and Chrysler Buildings were not lit up as they usually are. Retail shops still blasted their a/c high enough to be felt on the street, but enough other people pitched in to make it work.

Who didn't respond at all heroically, though, was the general population. Electric usage went up after 6pm, when people got home and cranked up their a/c.

On the one hand, who can blame them? It was miserable. Just the walk from the subway took a couple of hours to recover from.

However, I couldn't help but think: this is it, folks. Do you think it's going to get, on the whole, cooler in the years to come? Do you think we're modernizing our electric plants fast enough to keep up with increased demand? Do you think coal and oil will last forever, and even if they do, that it's a good thing to be pumping more and more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere?

We should be conserving every day, not just when there's an emergency. The problem is, no one is asking us to; no one is telling us to.

God on the Upper West Side

When I lived in the 70s, the proselytizers I ran into were mostly Jews for Jesus around the Christian holidays, and Lubavitchers in Mitzvah tanks around the Jewish ones. It made a sort of sense. There are a lot of secular Jews in that neighborhood; both sides probably thought a few were ready to be turned in their direction.

In the 90s, there are a lot of orthodox Jews, so neither of these groups probably think it's worth working here. What we do have are Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormons. The former are invariably middle-aged black women who speak Spanish. The latter, pairs of young white men in suits.

As I came out of the bagel store on Broadway this morning, there were two Mormons, bibles in hand, waiting on the sidewalk. I wasn't trying or not trying to avoid them, but as I passed, one said to the other, "nah," and I assumed they had decided not to pick on me.

Maybe they were just deciding not to go into the bagel store for a coffee, though, because they followed me across the street, to Starbucks. As we crossed, a man stopped at the light said to them, not meanly, "God is dead."

Outgoing atheists are another thing we have in my neighborhood, apparently.

In the 90s, there are a lot of orthodox Jews, so neither of these groups probably think it's worth working here. What we do have are Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormons. The former are invariably middle-aged black women who speak Spanish. The latter, pairs of young white men in suits.

As I came out of the bagel store on Broadway this morning, there were two Mormons, bibles in hand, waiting on the sidewalk. I wasn't trying or not trying to avoid them, but as I passed, one said to the other, "nah," and I assumed they had decided not to pick on me.

Maybe they were just deciding not to go into the bagel store for a coffee, though, because they followed me across the street, to Starbucks. As we crossed, a man stopped at the light said to them, not meanly, "God is dead."

Outgoing atheists are another thing we have in my neighborhood, apparently.

01 August 2006

Did the New Yorker kill Fidel Castro?

Last week, The New Yorker ran a story about what will happen to Cuba when Fidel Castro dies.

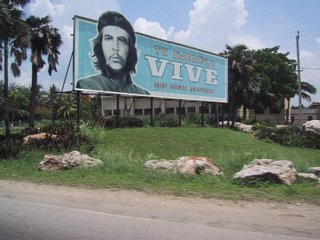

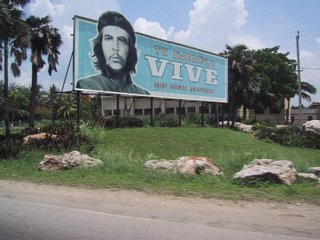

(This is not Castro, by the way; it's Che Guevara, of whom there are thousands of portraits all over Cuba.)

(This is not Castro, by the way; it's Che Guevara, of whom there are thousands of portraits all over Cuba.)

This morning, news comes that he is ill, and has ceded power temporarily to his brother and expected successor, Raul. There is speculation that he might already be dead, but no one really knows.

I went to Cuba in 2002, to an interactive media and art conference. This was during those few open years where such legal trips were not all that difficult to arrange, if you were going for work-related edu- cational reasons, and Cuba was well set-up to host these kinds of conferences. Despite its poverty, it was already a major tourist destination for Europeans and Latin Americans.

This was during those few open years where such legal trips were not all that difficult to arrange, if you were going for work-related edu- cational reasons, and Cuba was well set-up to host these kinds of conferences. Despite its poverty, it was already a major tourist destination for Europeans and Latin Americans.

The people were wonderful, generously saying that "we like Americans; we don't like your government." We told them that we didn't like our government much right then either.

Several older people spoke to me about the failure of the revolution; they considered themselves to still be revolutionaries. They didn't want free-market capitalism to take over when Fidel died. They thought the trade embargo should be tightened. It was the only way to hurt Castro, they said.

Several older people spoke to me about the failure of the revolution; they considered themselves to still be revolutionaries. They didn't want free-market capitalism to take over when Fidel died. They thought the trade embargo should be tightened. It was the only way to hurt Castro, they said.

Younger Cubans wouldn't talk about politics. "You can talk about it, but we cannot," the implication was that they could be arrested if the wrong person overheard them.

There is dancing in the streets today in Miami. The U.S. government relies on the exiled Cuban community for guidance on how to handle the transition. Because of course, we are only waiting for Castro to die, the smallest sliver of an opening to go barging in and take over. (Don't forget: Cuba has off-shore oil reserves.) My impression is that the exiles think they will be welcomed back to the island with open arms, and play important roles in bringing the country into the 21st century. I think they are in for a surprise.

When Fidel dies, things will change. The Cuban people deserve change. I only hope they get to say what kind of change it is they want, and that the United States doesn't make them change for the worse.

When Fidel dies, things will change. The Cuban people deserve change. I only hope they get to say what kind of change it is they want, and that the United States doesn't make them change for the worse.

(This is not Castro, by the way; it's Che Guevara, of whom there are thousands of portraits all over Cuba.)

(This is not Castro, by the way; it's Che Guevara, of whom there are thousands of portraits all over Cuba.)This morning, news comes that he is ill, and has ceded power temporarily to his brother and expected successor, Raul. There is speculation that he might already be dead, but no one really knows.

I went to Cuba in 2002, to an interactive media and art conference.

This was during those few open years where such legal trips were not all that difficult to arrange, if you were going for work-related edu- cational reasons, and Cuba was well set-up to host these kinds of conferences. Despite its poverty, it was already a major tourist destination for Europeans and Latin Americans.

This was during those few open years where such legal trips were not all that difficult to arrange, if you were going for work-related edu- cational reasons, and Cuba was well set-up to host these kinds of conferences. Despite its poverty, it was already a major tourist destination for Europeans and Latin Americans.The people were wonderful, generously saying that "we like Americans; we don't like your government." We told them that we didn't like our government much right then either.

Several older people spoke to me about the failure of the revolution; they considered themselves to still be revolutionaries. They didn't want free-market capitalism to take over when Fidel died. They thought the trade embargo should be tightened. It was the only way to hurt Castro, they said.

Several older people spoke to me about the failure of the revolution; they considered themselves to still be revolutionaries. They didn't want free-market capitalism to take over when Fidel died. They thought the trade embargo should be tightened. It was the only way to hurt Castro, they said. Younger Cubans wouldn't talk about politics. "You can talk about it, but we cannot," the implication was that they could be arrested if the wrong person overheard them.

There is dancing in the streets today in Miami. The U.S. government relies on the exiled Cuban community for guidance on how to handle the transition. Because of course, we are only waiting for Castro to die, the smallest sliver of an opening to go barging in and take over. (Don't forget: Cuba has off-shore oil reserves.) My impression is that the exiles think they will be welcomed back to the island with open arms, and play important roles in bringing the country into the 21st century. I think they are in for a surprise.

When Fidel dies, things will change. The Cuban people deserve change. I only hope they get to say what kind of change it is they want, and that the United States doesn't make them change for the worse.

When Fidel dies, things will change. The Cuban people deserve change. I only hope they get to say what kind of change it is they want, and that the United States doesn't make them change for the worse.